Sveta Dorosheva creates the key visual for the British Library’s Fantasy: Realms of Imagination Exhibition.

Garrick Webster interviews Sveta Dorosheva to find out more about her project with the British Library.

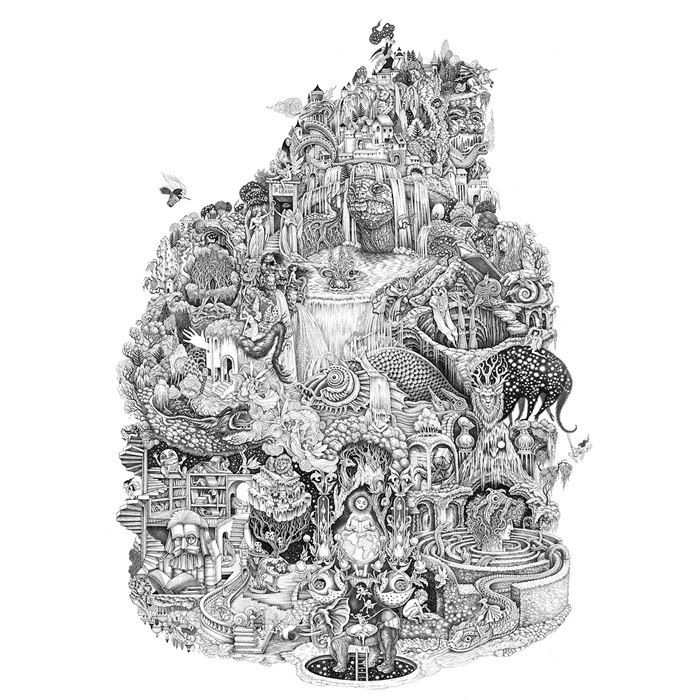

When the British Library planned its winter 2023 exhibition covering the fantasy genre, the curators wanted an illustrator capable of bringing together stories, myths and legends across the ages and from around the world. To create the key visual and a variety of supplementary illustrated elements they turned to Sveta Dorosheva.

Based in Israel, the Ukrainian artist brought her vast experience illustrating fairy tales, folklore and weird fiction to the project, working in her classic fantasy style. Below, Sveta talks about the complexities of the brief, how she approached the epic artwork, her working methods and how happy accidents can contribute to stunning fantasy imagery.

When and how did the job come about?

One of the curators of the exhibition saw a map I had created for Leigh Bardugo’s King of Scars, and the creative agency The Storycatchers got in touch with my agents at IllustrationX in spring 2023. I immediately agreed to it because one does not get to create a visual world covering the entire history of the fantasy genre very often.

What was the brief?

The task was to seamlessly weave together the four realms of fantasy literature represented at the exhibition – fairy tales and folklore; worlds and portals; epics and quests; and weird and uncanny – into a single composition populated with characters and imbued with different moods depending on the stories. In addition, the brief asked for 20 illustrated elements for chapter openers – some taken from the key visual, some new – which were combined with chapter title text. It was the best brief I’ve ever seen, technically succinct and well thought-out.

The key visual references 65 different stories, characters and settings. Which ones resonated with you most?

Gregor Samsa, as a cockroach, reading Kafka, is one of my favourites. I love absurdist literature and I think the new weird genre is growing because of the confusion and rapid change the world is going through, similar to the ‘old weird’ which flourished 100 years ago, which was also a period of incredible flux. If you wake up one day as a cockroach and are clueless as to what’s going on, you still have to carry on with your work.

There’s also a reference to Hieronymus Bosch’s tree man. This wasn’t in the brief; I just love Bosch. Another favourite is the underworld labyrinth, with seething snakes and a dreamlike figure at its centre. The brief mentioned a labyrinth, but I was after that feeling you get when you dream of weird places and encounters, then wake up and think, ‘Where was I?’

I took special pleasure in inserting characters reading books throughout the illustration. They weren’t in the brief but came naturally. The Earth is reading a book, standing on the world elephant under the tree of life. A stone giant is reading The Divine Comedy, reclining over the entrance to Hell with tiny figures of Dante and Virgil leaving the underworld.

What was your creative process?

The first stage is always the longest – research and ideas. I hardly draw at all but look at what’s in the brief and what has gone before and digest it. I procrastinate to the point of self-loathing, scrawl down some words and ideas, then sketch some thumbs to begin forming the composition. Then I disappear and work on the first draft.

What media do you use?

I draw by hand on paper. The first detailed draft, with so many characters, themes and landscapes in black and white, was drawn in pencil to figure out the tonal scheme. This was basically a finished A2 drawing. The final art was A1 and done in ink with a dipping drawing nib.

What feedback and amends did you receive?

The amends mainly involved the portals, which were reworked to suggest a subterranean library with secret passages and mysterious visitors. Although the brief was technically well defined, I had complete creative freedom. The content of the image was mostly accepted during the first round and we fine-tuned the technical aspects of the composition. It was a dream job for a dream client.

Including everything mentioned in the brief must have been challenging. How did you integrate all of it into a single image?

The initial composition was difficult to put together. Because everything is so closely interwoven, moving one element entailed redoing half the composition. Including so much in one image might seem like a challenge, but I was greedy – I wanted to draw everything in the brief, and more. So really the artwork was a labour of love.

Were there any happy accidents along the way?

When I was working on the underground library, one of my kids walked in and asked about the image. This never happens. I started explaining the optical illusion around the librarian made of books and pointed out the gargoyle and the fish, which is reading. He said, “You know what would be cool? A dinosaur reading.” He wouldn’t leave until I’d added one. I thought I’d erase it if it was questioned but it’s still there.

Where did the artistic inspiration come from?

I was aiming for the look and feel of the Golden Age fantasy illustrators – Arthur Rackham, Edmund Dulac, Kay Nielsen and others. I also borrowed from my favourite weird and fantastic art through the ages, such as Bosch, Bruegel and medieval illuminated manuscripts.

Where can people see the work?

It’s on the book cover for the exhibition, a banner at the entrance, a billboard at Euston, upright advertising at bus stops, is a piece of wall art in the library hall, and across the show’s merchandise. During the opening of the exhibition, it was projected across the British Library’s atrium all evening.

How have people responded to the work?

This artwork was a dream commission for me, and the response has been genuinely awesome. The illustration keeps people looking and finding, which is what I intended, and they always ask for a list of all the references. My favourite reaction is the joy of recognition and then seeing people look for more within the artwork.

Read more about the project here.